Spielberg’s tale of “science eventuality” opened to record-breaking box-office twenty-five years ago this summer, and for the occasion The Bits features a compilation of statistics and box-office data that places the movie’s performance in context, plus passages from vintage film reviews, a reference/historical listing of the movie’s digital sound presentations, and, finally, an interview segment with a trio of Spielberg authorities who discuss the film’s impact and legacy.

![On the set of "Blue Harvest" (aka Return of the Jedi)]()

JURASSIC NUMBER$

- 1 = Box-office rank among the Jurassic franchise (tickets sold and adjusted for inflation)

- 1 = Peak all-time box-office chart position (worldwide)

- 1 = Rank among top-earning films of 1993 (calendar year)

- 1 = Rank among top-earning films of 1993 (summer season)

- 1 = Rank among Universal’s all-time top-earning films at close of original run

- 2 = Peak all-time box-office chart position (domestic)

- 3 = Box-office rank among films directed by Spielberg (adjusted for inflation)

- 3 = Number of Academy Awards

- 3 = Number of weeks top-grossing movie (weeks 1-3)

- 3 = Rank among top-earning movies of the 1990s

- 5 = Number of films in Jurassic franchise

- 5 = Number of years holding #1 spot on list of all-time top-earning films

- 10 = Number of days to gross $100 million*

- 16 = Number of months between theatrical release and home video release

- 17 = Rank on current list of all-time top-grossing films (adjusted for inflation)

- 24 = Number of days to gross $200 million**

- 28 = Rank on current list of all-time top-grossing movies (worldwide)

- 29 = Rank on current list of all-time top-grossing movies (domestic)

- 68 = Number of days to gross $300 million**

- 71 = Number of weeks film was in theatrical release

- 876 = Number of digital sound presentations during first-run**

- 2,404 = Number of theaters playing the movie during opening week

- 2,565 = Peak number of theaters simultaneously showing the movie (week of July 9-15)

- $24.98 = Suggested retail price of initial home video release (VHS)

- $29.98 = Suggested retail price of initial home video release (CLV LaserDisc)

- $74.98 = Suggested retail price of initial home video release (CAV LaserDisc)

- $19,561 = Opening weekend per-screen-average

- $1.5 million = Amount paid to acquire rights to Crichton’s novel

- $3.1 million = Opening weekend box-office gross (June 10 sneak previews)**

- $17.6 million = Highest single-day gross (June 12)**

- $45.4 million = Domestic box-office gross (2013 3D re-release)

- $47.1 million = Opening weekend box-office gross (June 11-13)**

- $50.1 million = Opening weekend box-office gross (June 11-13 + June 10 sneaks)**

- $63.0 million = Production cost

- $71.1 million = International box-office gross (2013 3D re-release)

- $81.7 million = Opening week box-office gross (June 10-17)**

- $109.7 million = Production cost (adjusted for inflation)

- $316.6 million = Box-office gross during summer season (June 10 - Sept 6)

- $357.1 million = Domestic box-office gross (original release)

- $402.5 million = Cumulative domestic box-office gross

- $555.6 million = International box-office gross (original release)**

- $626.7 million = Cumulative international box-office gross

- $670.7 million = Cumulative domestic box-office gross (adjusted for inflation)

- $912.7 million = Worldwide box-office gross (original release)**

- $1.1 billion = Cumulative international box-office gross (adjusted for inflation)

- $1.1 billion = Cumulative worldwide box-office gross

- $1.7 billion = Cumulative worldwide box-office gross (adjusted for inflation)

*tied industry record

**established new industry record

![On the set of Return of the Jedi]()

A SAMPLING OF PASSAGES FROM REVIEWS

“The dinosaurs of Jurassic Park live and breathe. They will astonish you — and scare you. That’s why Steven Spielberg’s $51 million film is a rip-roaring hit, the most relentlessly exciting summer adventure since his Raiders of the Lost Ark back in 1981.” — Jack Garner, Gannett News Service

“Jurassic Park puts us in the hands of a master movie-maker who knows how to manipulate every last shred of suspense and wonder from us. By the end of the movie, you’re left exhausted but exhilarated. It’s that good.” — Marylynn Uricchio, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

“The greatly anticipated Jurassic Park, it turns out, is the poor little rich kid of this summer’s movies. Everything that money can buy has been bought, and what an estimated $60 million can purchase is awfully impressive. But even in Hollywood there are things a blank check can’t guarantee and the lack of those keeps this film from being more than one hell of an effective parlor trick.” — Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times

“You won’t believe your eyes. Jurassic Park is colossal entertainment — the eye-popping, mind-bending, kick-out-the-jams thrill ride of the summer and probably the year.” — Peter Travers, Rolling Stone

“On paper, this story is tailor-made for Mr. Spielberg’s talents, combining the scares of Jaws with the high-tech, otherworldly romance of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and of course adding the challenge of creating the dinosaurs themselves. Yet once it meets reality, Jurassic Park changes. It becomes less crisp on screen than it was on the page, with much of the enjoyable jargon wither mumbled confusingly or otherwise thrown away. Sweetening the human characters, eradicating most of their evil motives and dispensing with a dinosaur-bombing ending (so the material is now sequel-friendly), Mr. Spielberg has taken the bite out of this story. Luckily, this film’s most interesting characters have teeth to spare.” — Janet Maslin, The New York Times

“[T]he special-effects wizards worked their magic and the result is beyond belief. Jurassic Park is a blockbuster in the best sense of the word. From the opening scene to the closing credits, it grabs the audience and holds it in thrall, making us believe in things that can’t possibly be real… yet.” — Nanciann Cherry, The (Toledo) Blade

“If Spielberg’s Jurassic zoo is in every way remarkable, however, his human actors are left with sketchy, comic-book characterizations and plot lines that fray and dangle.” — Steven Rea, The Philadelphia Inquirer

“Steven Spielberg’s spectacular Jurassic Park has raptors and brachiosaurs and more, oh-my! than any movie in recent memory. It’s a sinfully entertaining, state-of-the-art summer blockbuster whose myriad nonstop thrills easily exceed its mega-hype.” — Eleanor Ringel, The Atlanta Constitution

“Spielberg’s gonzo special effects flick seems to put dinosaurs right in the multiplex. So real you may never feel comfortable in a toilet stall again. But scary? Nah, not if you’re over 10. ” — Judy Gerstel, Detroit Free Press

“Forgive the relentless promotion, the advance publicity, the ’action figures’ turning up in toy stores, and the dinosaurs you’ll be seeing everywhere for the next few months. Get over feeling bombarded, because if you don’t you’ll be missing one great monster movie.” — Mick LaSalle, San Francisco Chronicle

“The dinosaurs in this monster of all monster movies are nothing if not awesome — and they have to be, because the rest of the movie, while frequently suspenseful, is disappointingly routine. If only the humans were as impressive. — Jeff Shannon, The Seattle Times

“Director Steven Spielberg is back at the top of his form as master of Hollywood spectacle. He spent tens of millions of dollars on the special effects and spent it so well that you can hardly tell whether you’re seeing a movie or receiving 5,000 jolts of pure Spielbergian movie magic. Jurassic Park combines the wonder of E.T. with all the terrifying thrills of Jaws.” — Bob Fenster, The (Phoenix) Arizona Republic

“In theory, Jurassic Park is Jaws plus Frankenstein: A thrill-ride plot propelled by the most potent movie monsters since Spielberg’s fish swallowed most of Long Island Sound combined with a cautionary tale about the dangers of tampering with nature. In execution, alas, Jurassic Park falls short of delivering either the pulpy, don’t-go-near-the-water thrills of Jaws or Frankenstein’s primal horror of science run amok. Burdened by a clunky script that relies too heavily on mechanical jolts and special effects, and skimpily written characters who amount to nothing more than dinosaur prey, it’s closer to a Gold Card version of a Godzilla movie. Why did these seasoned pros, working with seemingly unlimited sums of money, plow into production with an unpolished script? It’s absolutely baffling. One can only conclude that they were as dumbly transfixed by Stan Winston’s lifelike dinosaurs as the characters are — and poor Laura Dern and Sam Neill are called upon to play open-mouthed awe far too many times for anyone over the age of 12.” — Joanna Connors, The (Cleveland) Plain Dealer

“Jurassic Park will at least disabuse anyone of the idea that it would be fun to share the planet with dinosaurs. Steven Spielberg’s scary and horrific thriller may be one-dimensional and even clunky in story and characterization, but it definitely delivers where it counts, in excitement, suspense and the stupendous realization of giant prehistoric reptiles. Having finally found another set of Jaws worthy of the name, Spielberg and Universal have a monster hit on their hands.” — Todd McCarthy, Variety

“It’s a good thing the effects are so solid, because they have to carry virtually all of the emotional charge of the picture. Where Spielberg was able to supply Jaws and Close Encounters with a powerful psychological subtext, centered on threats and tensions within the nuclear family, Jurassic Park plays largely on the surface, without the resonance that gives meaning to the thrills and turns a well-told adventure yarn into our modern equivalent of mythology.” — Dave Kehr, Chicago Tribune

“Jurassic Park is amazing.” — Richard Corliss, Time

“When young Steven Spielberg was first offered the screenplay for Jaws, he said he would direct the movie on one condition: That he didn’t have to show the shark for the first hour. By slowly building the audience’s apprehension, he felt, the shark would be much more impressive when it finally arrived. He was right. I wish he had remembered that lesson when he was preparing Jurassic Park, his new thriller set in a remote island theme park where real dinosaurs have been grown from long-dormant DNA molecules. The movie delivers all too well on its promise to show us dinosaurs. We see them early and often, and they are indeed a triumph of special effects artistry, but the movie is lacking other qualities that it needs even more, such as a sense of awe and wonderment, and strong human story values.” — Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times

“Jurassic Park is a fun-house with humor, thrills and heart. It has the spine-tingly magic of Steven Spielberg’s best work. Go, tremble and enjoy.” — David Ansen, Newsweek

“Even at his most mechanical, Spielberg brings a sense of wonder to a project, and usually manages to add some wit, too. Thus the theme park in Jurassic Park is the perfect parody of theme parks, down to the Walt-like character played by Attenborough, who appears in a video to introduce a cartoon explaining DNA. Later, when the camera pans the park’s gift shop, you see the very T-shirts, candy and stuffed dinos that Universal will be peddling in ’real’ life for years to come. Yes, it’s cynical. It’s also hilarious.” — Bill Cosford, The Miami Herald

“One of the ironies here is that to make this anti-control-freak movie you’ve got to be a supreme control freak — Spielberg brought this complicated production in ahead of schedule (despite a hurricane) and under budget. It shows. Jurassic Park doesn’t match the heart of Close Encounters of E.T. or Empire of the Sun. With Jurassic Park Spielberg seems to have asked more of himself than to bring to the screen Hollywood’s ultimate theme park ride in the guise of an anti-theme park movie. This he does, riding those special-effects dinosaurs to pay dirt. It’s the work of a great field marshal.” — Jay Carr, The Boston Globe

![A scene from Return of the Jedi]()

THE DTS PRESENTATIONS

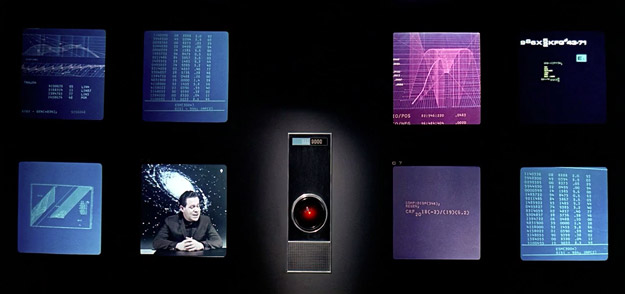

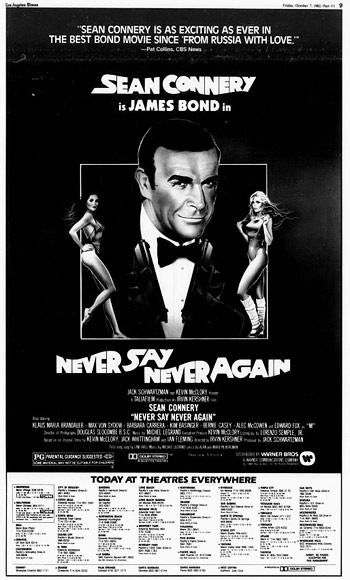

Jurassic Park was the first motion picture released in Digital Theater Systems (DTS) and the first batch of theaters to install the system and present Jurassic Park in the format are identified below.

The theaters screening the DTS presentation of Jurassic Park were arguably the best in which to experience the movie and the only way at the time to faithfully hear the movie’s award-winning discrete multichannel audio mix and with incredible sonic clarity.

The playback layout for DTS’s digital audio format was in a 5.1-channel configuration: three discrete screen channels + two discrete surround channels + low-frequency enhancement. Unlike competitor formats, however, which placed their digital audio directly on the film prints, DTS was engineered in a fashion whereby the audio was placed on Compact Disc(s) and synchronized via timecode running along the edge of the image on the 35mm prints.

While the DTS timecode was present on each and every print of the movie, discs were shipped only to the theaters that installed the requisite playback equipment. The prints also included a conventional Dolby Stereo analog soundtrack which eliminated the need for multiple print inventory and also served as a secondary audio backup should the digital playback ever fail.

Initially, DTS was offered in two versions: (1) DTS-6, a discrete 6-track (i.e. 5.1) mix and (2) DTS-S, a matrixed, 4-channel Lt-Rt stereo mix. The 6-track presentations, where known, are identified in the listing below with an asterisk. (Eventually, the DTS-S format was discontinued.)

Prior to the release of Jurassic Park in June 1993, there were un-promoted DTS test screenings of some Universal Studios releases including Dr. Giggles and The Public Eye.

In the months leading up to the release of Jurassic Park, director Steven Spielberg issued an explanation to motion picture exhibitors as to why he wanted his movie released with DTS audio.

“I’ve heard what my T-Rex sounds like roaring on 35mm Dolby Stereo, and I’ve heard the same roar produced for DTS equipment.”

Spielberg added:

“Raiders of the Lost Ark and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (among others) are two of my films that featured sounds and music in a fashion that, when experienced in 70mm six-track magnetic stereo, was virtually a different experience from when enjoyed in 35mm Dolby Stereo theaters. Only 200 theaters were able to exhibit Close Encounters and Raiders with the sound experience I intended. In that sense, very few moviegoers really received the full, head-on force of both of those films. Now, years later, along comes Jurassic Park — a sound experience you will never forget, available not only in those (premiere) 70mm houses, but now, thanks to DTS, in 35mm theaters that carry this new state-of-the-art equipment.”

Jurassic Park was at the time the industry’s widest release of a film featuring digital sound, and in this one release DTS vastly exceeded the number of Dolby Digital, SDDS and Cinema Digital Sound installations and with it launched a movie sound revolution. (The DTS competitors used, initially, a different strategy on their implementation by primarily targeting premiere venues in major markets.)

The listing includes the DTS engagements of Jurassic Park that commenced June 11th, 1993. (Some theaters began their run with sneak preview screenings on the 10th.) The listing does not include any mid-run DTS installations, move-over or subsequent bookings, nor does it include any international presentations or any of the movie’s thousands of standard analog presentations. (The world premiere of Jurassic Park was held June 9th, 1993, at the Uptown in Washington, DC.)

For the sake of stylistic consistency and clarity, some liberties have been taken in regard to some of the generically named cinemas in which the movie played. If, for instance, such a venue were located in a shopping center, effort has been made to identify the venue in this work whenever possible by the name of the shopping center even if, technically, such wasn’t the actual name of the venue.

Typically the total number of screens in a multiplex have been cited here even though in numerous cases a “complex” consisted of screens spread out among separate buildings.

In numerous cases two (or more) prints of Jurassic Park were shipped to theaters to increase the number of screenings of the movie per day and to allow a greater variety of start times. In a few of these cases the movie was shown in DTS on more than one screen but such cases are cited only once in the listing. Typically any multi-screen bookings were in DTS only on one of the screens and in analog Dolby Stereo on the other screen(s).

In a few cases, a city name has changed since 1993 (due to annexation, incorporation or a redrawing of municipality boundaries) and effort has been made to list these instances according to the city or recognized name at the time of the Jurassic Park engagement.

So, for historical reference, the first-run North American theaters that screened Jurassic Park with DTS audio were….

*6-Track DTS (any non-asterisked entries presumably screened the Lt-Rt version of DTS)

**Version Francaise (Le Parc Jurassique)

[On to Page 2]

[Back to Page 1]

![A scene from Return of the Jedi]()

THE 70MM ENGAGEMENTS

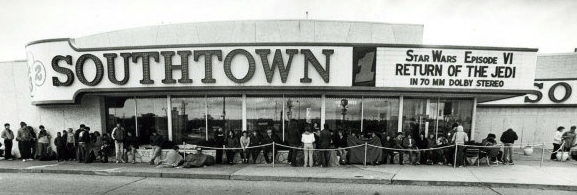

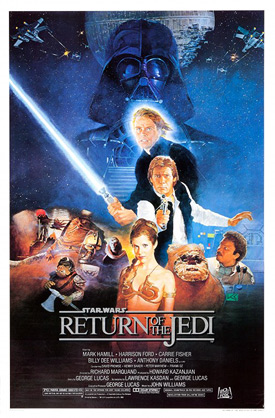

Event and prestige movies (what we might refer today as a tent-pole or high-profile release) have on occasion been given a deluxe release in addition to a conventional release. This section of the article includes a reference / historical listing of the first-run 70mm Six-Track Dolby Stereo premium-format presentations of Return of the Jedi in the United States and Canada. These were arguably the best theaters in which to have experienced Jedi and the only way to have faithfully heard the movie’s discrete multichannel audio mix. This is the sort of listing (sans the duration figures) that might’ve trended on the Internet to assist moviegoers in finding a 70mm presentation near them had such a resource existed in 1983.

Of the 150+ movies released during 1983, Return of the Jedi was among only thirteen to have 70mm prints prepared for selected engagements. Only about fifteen percent of Jedi’s initial print run was in the deluxe 70mm format, which offered superior audio and image quality but were significantly more expensive and labor-intensive to manufacture compared with conventional 35mm prints.

With a reported 164 large-format prints for North America (plus more for international release), Jedi was at the time the industry’s largest 70mm release and remains to this day among the industry’s ten largest such releases.

The 70mm prints of Jedi were intended to be projected in a 2.20:1 aspect ratio and were blown up from 35mm anamorphic. The noise-reduction and signal-processing format of the prints was Dolby “A,” and the soundtrack was Dolby processor setting Format 42 (i.e. three discrete screen channels + one discrete surround channel + “baby boom” low-frequency enhancement).

For the release of Jedi, Lucasfilm introduced the THX Sound System (in two markets) and (unofficially) introduced their Theatre Alignment Program (TAP) to evaluate and approve the theaters selected to book a 70mm print.

Seventy-millimeter trailers for The Star Chamber, To Be or Not to Be and Brainstorm circulated during the Jedi release and which were recommended to be screened with the 70mm presentations.

The listing includes the 70mm engagements that commenced May 25th, 1983 (except where noted otherwise). The listing does not include the movie’s thousands of standard 35mm engagements (though if any readers are interested many of these bookings were cited in our previous Jedi retrospective).

The duration of the engagements (measured in weeks) has been included in parenthesis following the cinema name.

Note that some of the presentations included in this listing were presented in 35mm during the latter weeks of the engagement because the booking was moved to a smaller, 35mm-only auditorium within a multiplex or due to print damage and the distributor’s unwillingness to supply a 70mm replacement print. As well, the reverse was true in some cases whereas a booking began with a 35mm print because the lab was unable to complete the 70mm print order in time for an opening-day delivery or the exhibitor negotiated a mid-run switch to 70mm. In these cases, the 35mm portion of the engagement has been included in the duration figure.

Some liberties have been taken in regard to generically named theaters (i.e. “Cinema,” “Cinema Twin,” “Cinema 6,” etc.). Typically such venues were located in shopping centers and as such they have been identified in this work whenever possible by the name of the shopping center even if, technically, such wasn’t the actual name of the venue.

Regarding multiplex venues, effort has been made to identify the total number of screens in a complex during the Jedi engagement even if in some situations a “complex” consisted of screens spread out among separate buildings. Additionally, simplified nomenclature for the sake of stylistic consistency has been utilized for venue screen counts (i.e. “twin,” “triplex,” “4-plex,” etc.) instead of retaining the (often inconsistent) individualistic usage of numbers or Roman numerals that may have been present in advertising or used on marquees. In cases where it is known Jedi was screened simultaneously in 70mm in more than one auditorium in a complex, both engagements have been cited but the numbers provided represent the prints and do not necessarily reflect the auditorium number in which the film was playing.

In a couple of cases, a city name has changed since 1983 (due to annexation or incorporation) and effort has been made to list these cases according to the city or recognized name at the time of the Jedi engagement.

Prior to release, in lieu of a formal premiere for Return of the Jedi, Lucasfilm and Fox chose to hold regional charity previews between May 22nd and 24th. The cities in which these screenings were held included Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Dallas, Denver, Flint, Los Angeles, New York, Oakland, San Francisco, Toronto, and Tucson. As well, the movie was screened as a part of the Seattle International Film Festival.

So, which theaters in North America screened the 70mm version of Return of the Jedi?

![70 mm]()

ALABAMA

- Birmingham — Cobb’s Village East Twin (19)

ALASKA

- Anchorage — Wometco-Lathrop’s Polar Triplex (24) [opened June 3rd]

![A 70 mm film frame for Return of the Jedi]()

ALBERTA

- Calgary — Famous Players’ Palace (18)

- Edmonton — Famous Players’ Londonderry Twin (19)

- Edmonton — Famous Players’ Westmount Twin (21)

ARIZONA

- Phoenix — UA’s Chris-Town Mall 6-plex (29)

- Scottsdale — Nace’s Kachina (17)

- Tucson — Plitt’s Foothills 4-plex (25)

- Tucson — TM’s El Con 6-plex (41)

BRITISH COLUMBIA

- Vancouver — Odeon’s Vogue (21)

- Victoria — Odeon’s Haida (18)

CALIFORNIA

- Campbell — UA’s Pruneyard Triplex (38)

- Cerritos — UA’s Cerritos Mall Twin (24)

- Corte Madera — Marin’s Cinema (18)

- Costa Mesa — Edwards’ Town Center 4-plex (25)

- El Cajon — UA’s Parkway Plaza Triplex (23)

- Hayward — UA’s Hayward 5-plex (40)

- La Mirada — Pacific’s La Mirada Mall 6-plex (29)

- Long Beach — UA’s Marketplace 6-plex (21)

- Los Angeles (Del Rey) — UA’s Marina Marketplace 6-plex (23)

- Los Angeles (Hollywood) — UA’s Egyptian Triplex (21)

- Los Angeles (North Hollywood) — UA’s Valley Plaza 6-plex (22)

- Los Angeles (Westwood Village) — GCC’s Avco Center Triplex (20) [THX]

- Los Angeles (Woodland Hills) — UA’s Warner Center 6-plex (22)

- Montclair — UA’s Towne Center Plaza 6-plex (28)

- Monterey — UA’s Cinema 70 (18)

- National City — Pacific’s Sweetwater 6-plex (#1: 41)

- National City — Pacific’s Sweetwater 6-plex (#2: 6)

- Newport Beach — Edwards’ Newport Twin (17)

- Oakland — Foster’s Piedmont (18)

- Orange — Syufy’s Cinedome 6-plex (#1: 22)

- Orange — Syufy’s Cinedome 6-plex (#2: 11)

- Palm Springs — Metropolitan’s Camelot Triplex (17)

- Pleasant Hill — Syufy’s Century 5-plex (28)

- Redwood City — UA’s Redwood 6-plex (41)

- Riverside — UA’s Tyler Mall 4-plex (41)

- Sacramento — UA’s Arden Fair 6-plex (51)

- San Diego — Pacific’s La Jolla Village 4-plex (21)

- San Diego — UA’s Glasshouse 6-plex (22)

- San Francisco — UA’s Coronet (28)

- Santa Barbara — Metropolitan’s Arlington (16)

- Santa Clara — UA’s Cinema 150 (29)

- Thousand Oaks — UA’s Oaks 5-plex (21)

- Westminster — UA’s Westminster Mall Twin (29)

COLORADO

- Colorado Springs — Commonwealth’s Cooper Triplex (19)

- Denver — Commonwealth’s Continental (7) [early termination due to theater fire]

- Denver — Commonwealth’s Cooper Twin (20+)

CONNECTICUT

- Orange — Redstone’s Showcase 7-plex (18)

- Stamford — Trans-Lux’s Ridgeway Twin (12)

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

- Washington — Circle’s MacArthur Triplex (15)

- Washington — GCC’s Jenifer Twin (18)

FLORIDA

- Fort Lauderdale — GCC’s Galleria 4-plex (16)

- Kendall — Wometco’s Dadeland Triplex (18)

- Miami Beach — Wometco’s Byron Carlyle Triplex (10)

- North Miami Beach — Wometco’s 163rd Street Triplex (21)

- Orlando — GCC’s Fashion Square 6-plex (24)

- Winter Park — Wometco’s Winter Park Triplex (18)

GEORGIA

- Atlanta — Plitt’s Phipps Plaza Triplex (23)

HAWAII

- Honolulu — Consolidated’s Cinerama (24) [opened June 24th]

![Screenings for Star Wars in 1983]()

![Screenings for Star Wars in 1983]()

ILLINOIS

- Belleville — BAC’s Cinema (18)

- Calumet City — Plitt’s River Oaks 6-plex (16)

- Chicago — GCC’s Ford City Triplex (19)

- Chicago — Plitt’s Esquire (16)

- Chicago — Plitt’s State Lake (8)

- Forest Park — Essaness’ Forest Park Mall Triplex (22)

- Lombard — GCC’s Yorktown Triplex (19)

- Moline — Redstone’s Parkway (21)

- Niles — Essaness’ Golf Mill Triplex (15)

- Northbrook — Center’s Edens Twin (16)

- Schaumburg — Plitt’s Woodfield 4-plex (18)

- Tinley Park — Essaness’ Bremen 4-plex (19)

INDIANA

- Evansville — Stieler’s North Park 7-plex (19)

- Fort Wayne — MSM’s Holiday Twin (21)

- Indianapolis — Y&W’s Eastwood (18)

![A newspaper ad for Return of the Jedi]()

IOWA

- Des Moines — Dubinsky’s River Hills (26)

- Dubuque — Dubuque’s Cinema Center 5-plex (17)

KANSAS

- Overland Park — Dickinson’s Glenwood Twin (21)

- Wichita — Commonwealth’s Twin Lakes Twin (21)

- Wichita — Dickinson’s Mall (18)

KENTUCKY

- Florence — Mid States’ Florence 6-plex (41)

- Louisville — Redstone’s Showcase 9-plex (29)

LOUISIANA

- Metairie — GCC’s Lakeside 5-plex (18)

MANITOBA

- Winnipeg — Odeon’s Grant Park (19)

MASSACHUSETTS

- Boston — Sack’s Charles Triplex (17)

- Chestnut Hill — GCC’s Chestnut Hill 5-plex (18)

- Seekonk — Redstone’s Showcase 7-plex (18)

- West Springfield — Redstone’s Showcase 9-plex (18)

MICHIGAN

- Dearborn — UA’s The Movies at Fairlane 10-plex (29)

- Flint — Butterfield’s Flint (25)

- Livonia — NGT’s Mai Kai (18)

- Southfield — NGT’s Americana 4-plex (27)

- Southgate — NGT’s Southgate Triplex (19)

- Troy — UA’s The Movies at Oakland 5-plex (23)

MINNESOTA

- Bloomington — GCC’s Southtown Twin (21)

- Minneapolis — Plitt’s Skyway 4-plex (17)

- Minnetonka — Plitt’s Ridge Square Triplex (19)

- Roseville — GCC’s Har-Mar 11-plex (21)

- West St. Paul — Engler’s Signal Hills 4-plex (18)

MISSOURI

- Hazelwood — Mid-America’s Village Triplex (29)

- Independence — Mid-America’s Blue Ridge East 5-plex (18)

- Kansas City — Commonwealth’s Bannister Mall 5-plex (18)

- Richmond Heights — Mid-America’s Esquire 4-plex (17)

NEBRASKA

- Omaha — Commonwealth’s Indian Hills Twin (29)

- Omaha — Douglas’ Q Cinema 6-plex (22)

NEVADA

- Las Vegas — Syufy’s Cinedome 6-plex (15+)

NEW JERSEY

- Edison — GCC’s Menlo Park Twin (18)

- Lawrenceville — Sameric’s Eric Lawrenceville Twin (21)

- Moorestown — Sameric’s Eric Plaza Moorestown Twin (29)

- Paramus — RKO Century’s Route Four 7-plex (21)

- Sayreville — Redstone’s Amboy 10-plex (13)

NEW MEXICO

- Albuquerque — GCC’s Louisiana Blvd. Triplex (18)

![Screenings for Star Wars in 1983]()

NEW YORK

- Colonie — RKO Century’s Fox Colonie Twin (21)

- East Meadow — UA’s Meadowbrook 4-plex (16)

- Garden City — RKO Century’s Roosevelt Field Triplex (17)

- Hicksville — RKO Century’s Mid-Island Plaza Twin (18)

- New York (Brooklyn) — RKO Century’s Kingsway 4-plex (21)

- New York (Manhattan) — Loews’ 34th Street Showplace Triplex (16)

- New York (Manhattan) — Loews’ Astor Plaza (21)

- New York (Manhattan) — Loews’ Orpheum Twin (16)

- Pittsford — Loews’ Pittsford Triplex (23)

- Valley Stream — Redstone’s Sunrise 11-plex (17)

- Yonkers — GCC’s Central Plaza Twin (18)

NORTH CAROLINA

- Charlotte — Plitt’s Park Terrace Triplex (19)

- Winston-Salem — Plitt’s Thruway Twin (23)

NOVA SCOTIA

- Halifax — Famous Players’ Scotia Square (18)

OHIO

- Beavercreek — Mid States’ Beaver Valley 6-plex (18)

- Dayton — Chakeres’ Dayton Mall 8-plex (18)

- Springdale — Mid States’ Tri-County Cassinelli Square 5-plex (41)

- Toledo — Redstone’s Showcase Triplex (28)

ONTARIO

- Hamilton — Famous Players’ Tivoli (18)

- London — Famous Players’ Park (18)

- North York — Famous Players’ Towne & Countrye Twin (19)

- Ottawa — Odeon’s Somerset (18)

- Scarborough — Famous Players’ Cedarbrae 6-plex (19)

- Toronto — Famous Players’ Cumberland 4-plex (10) [La Reserve]

- Toronto — Famous Players’ Runnymede Twin (19)

- Toronto — Famous Players’ University (21) [includes TIFF interruption Sept 9-17]

OREGON

- Beaverton — LT’s Westgate Triplex (29)

- Portland — Moyer’s Rose Moyer 6-plex (41)

PENNSYLVANIA

- Allentown — Sameric’s Eric Allentown 5-plex (28)

- Easton — Sameric’s Eric Easton 4-plex (13)

- Harrisburg — Sameric’s Eric East Park Center Twin (18)

- Montgomeryville — Sameric’s Eric Montgomeryville Triplex (#1: 28)

- Montgomeryville — Sameric’s Eric Montgomeryville Triplex (#2: 2)

- Philadelphia — Sameric’s SamEric Triplex (#1: 28)

- Philadelphia — Sameric’s SamEric Triplex (#2: 2)

- Philadelphia — Sameric’s SamEric Triplex (#3: 2)

![A newspaper ad for Return of the Jedi]()

QUEBEC

- Montreal — United’s Claremont (13) [opened May 27th]

- Montreal — United’s Imperial (18)

- Montreal — United’s Le Parisien 5-plex (25) [opened June 22nd, Version Francaise]

- Ste-Foy — United’s Canadien (7)

RHODE ISLAND

- Warwick — Redstone’s Showcase 8-plex (18)

TENNESSEE

- Nashville — Martin’s Belle Meade (18)

TEXAS

- Addison — UA’s Prestonwood Creek 5-plex (29) [THX]

- Austin — GCC’s Highland Mall Twin (25)

- Dallas — GCC’s Northpark West Twin (21) [THX]

- Fort Worth — UA’s Hulen 6-plex (18)

- Houston — GCC’s Meyerland Plaza Triplex (21)

- San Antonio — Santikos’ Northwest 10-plex (29)

UTAH

- Riverdale — Tullis-Hansen’s Cinedome 70 Twin (15+)

- Salt Lake City — Plitt’s Centre (21) [includes temporary m/o to Regency, June 3-16]

- South Salt Lake — Syufy’s Century 5-plex (#1: 43)

- South Salt Lake — Syufy’s Century 5-plex (#2: 8)

VIRGINIA

- Springfield — GCC’s Springfield Mall 6-plex (18)

WASHINGTON

- Seattle — UA’s Cinema 150 (29)

WISCONSIN

- Milwaukee — UA’s Southgate (19)

- Wauwatosa — UA’s Mayfair (17)

- West Allis — Marcus’ Southtown Triplex (19)

ADDITIONAL / SUBSEQUENT 70MM ENGAGEMENTS

- 1983-07-22 … Thornton, CO — Commonwealth’s North Star Drive-In (4+) [m/o from Continental]

- 1983-07-29 … Toronto, ON — Famous Players’ Palace Triplex (9)

- 1983-09-30 … Montreal, QC — United’s York (4) [m/o from Imperial]

- 1983-10-21 … San Rafael, CA — Marin’s Regency 6-plex (7)

- 1983-10-21 … Toronto, ON — Famous Players’ Uptown 5-plex (8) [m/o from University]

- 1983-12-16 … Montreal, QC — United’s Imperial (3) [Version Francaise; m/o from Le Parisien]

- 1983-12-21 … Carmel, IN — Heaston’s Woodland Twin (4) [second run/discounted admission]

- 1983-12-23 … Cleveland, OH — Variety (3) [second run/discounted admission]

- 1983-12-23 … New York, NY — RKO Century’s Warner Twin (3)

- 1983-12-26 … Atlanta, GA — Fox (5 days) [Holiday Film Festival]

- 1984-03-28 … Toronto, ON — Cinesphere (5 days) [70mm Film Festival]

Though its 70mm prints have not been cited in this work, it should be pointed out that Return of the Jedi was re-released on March 29th, 1985, and in Special Edition form in 35mm with digital sound on March 14th, 1997. And over the years there have been numerous additional 70mm screenings, often for charity (including Star Wars triple features, ILM tributes, THX Sound System demonstrations, 70mm festivals, and 20th Century Fox retrospectives).

![A pair of one sheets for Return of the Jedi]()

[On to Page 3]

[Back to Page 2]

THE Q&A

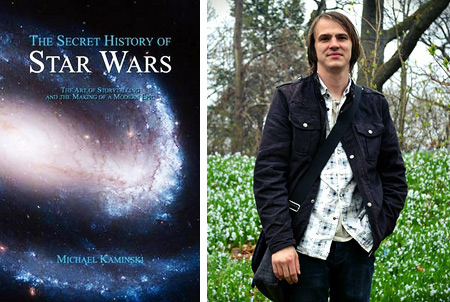

Michael Kaminski is the author of The Secret History of Star Wars: The Art of Storytelling and the Making of a Modern Epic (2008, Legacy).

![jedi35th kaminski]()

Mark O’Connell is the author of Watching Skies: Star Wars, Spielberg and Us (2018, The History Press).

![Mark O’Connell]()

Craig Stevens is the author of The Star Wars Phenomenon in Britain: The Blockbuster Impact and the Galaxy of Merchandise, 1977-1983 (2018, McFarland).

![Craig Stevens]()

The interviews were conducted separately and have been edited into a “roundtable” conversation format.

![A scene from Return of the Jedi]()

Michael Coate (The Digital Bits): How do you think Return of the Jedi should be remembered on its 35th anniversary?

Michael Kaminski: The 35th anniversary of Return of the Jedi comes just as Marvel Studios celebrates its 10th anniversary and the release of Infinity War, and I think there are a lot of parallels to be drawn in terms of bringing an ambitious, multi-film saga to a close. I struggle to think of a film series before the Star Wars trilogy which had a multi-movie storyline with the scale and scope that we ended up with in Return of the Jedi. Star Wars broke every box office record in history so of course sequels were going to be made, and we could have had another 10 years of 20th Century Fox cranking out a string of sequels to varying degree of success, and if you look at some of the early Expanded Universe like Splinter of the Mind’s Eye you get a window into this alternate world, but George Lucas took a different approach of making a three-film arc that told a larger tale. This is nothing special today, but before there was Marvel Studios or Harry Potter — which, it should also be noted, were simply adapting pre-existing literary works — Return of the Jedi did something truly unique by offering a satisfying capper to the story that began in 1977. Lucas also was ahead of his game in building in-roads to further the franchise, despite the finale of the third film — offering three more “prequels” set before the trilogy, and leaving the door open to continue the further adventures of the heroes or explore other areas of the world he had created in a cross-hatching “cinematic universe” before that term existed. It’s hard to see Return of the Jedi with fresh eyes and be truly staggered at the level of ambition and risk this approach had when the films were among the most popular and expensive ever made. Marvel Studios is getting massive accolades now as re-writing the book on franchise-building and world-building, but they are really just elaborating upon the example of the Star Wars series that only became apparent with the release of Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi — really, a two-part expansion of Star Wars from a fairy tale into a saga, that didn’t just make more sequels but turned towards personal melodrama and a three-part epic, in something that wasn’t adapting pre-existing sources but being made in real-time as a wholly original tale exclusive to the cinema. Even though each entry has an “episode” number, what makes the two sequels unique is that they are decidedly not episodic, but instead the second and final acts of a classic three-act narrative structure. To do this with a fantasy epic set in space on such a large budget would still be impressive today, decades later. Given the landscape of Hollywood in the early 21st Century, Return of the Jedi is prophetic.

Yes, a huge part of the movie drags due to Ewoks, yes, the writing isn’t as clever as before, but Return of the Jedi, for all its flaws, was attempting something not done before. It was this film that we finally got “the trilogy,” still intoned with sacredness all these decades later.

I also think that Return of the Jedi stands as the crowning achievement of visual and special effects from the pre-digital era. Hand-painted mattes, models, puppets, and optical compositing reached a level of complexity and ingenuity that had never been seen before, and I would also say since. If anyone knows anything about optical compositing, the space battle over Endor is a masterclass of optical effects so mind-bogglingly complex, with its hundreds of layers and dizzying motion-tracked camera moves, that it can still compete with the best and most state-of-the-art action scenes of films made over 30 years later like Rogue One. It’s reasons like this that the history of cinema is being shortchanged with the original theatrical versions of these films not being released in new remasters.

Mark O’Connell: Instead of closing the lid on the Star Wars saga and despite its story finality, Return of the Jedi is one of the reasons the franchise continued cinematically. Admiral Ackbar, Mon Mothma, Emperor Palpatine, Nien Nunb, Wicket W. Warwick, Bib Fortuna, Jabba the Hutt, the Biker Scouts, the Ewoks and the Speeder Bikes are all last act ingredients which — instead of celebrating the final hurrah — create story worlds, audience enthusiasm, cool sidebar industries, and an adoration which fed into the momentum of post-1983 Star Wars. The diplomacy and political gravitas of Mon Mothma is all over the prequels, the Ackbar sense of commanding during battle is a major last act device of 2016’s Rogue One via Admiral Raddus, the alien gangster enclave of Jabba’s Palace reverberates in The Force Awakens, and the adventure and speed of the Speeder Bike chase has been furthered in every Podrace, Coruscant night chase, Geonosis pursuit and escape from Canto Bight since.

And aside from being the first Star Wars movie that is finally an all-out war in the stars, Return of the Jedi is also responsible for the first Episode VII and Episode VIII — in the guise of the sometimes-overlooked Ewok TV movies, Caravan of Courage (aka The Ewok Adventure, 1984) and The Battle for Endor (1985).

Craig Stevens: I think that it should be remembered as a fantastic addition to the Star Wars film saga that brought the original Star Wars trilogy to an exciting and satisfying conclusion. It introduced a host of fantastic characters and environments. People can think back to so many wonderful moments in the film, even if they haven’t seen it in years.

![A scene from Return of the Jedi]()

Coate: Can you recall the first time you saw Jedi?

Kaminski: I was too young to see the films in theaters, so the first time I saw it was from family friends taping it off of HBO for me in the mid-late 1980s, knowing that I liked the first two films so much. Return of the Jedi always bored me the most out of all the films when I was a child, and it still does. Star Wars was a lot of fun, and Empire Strikes Back just looked and felt so interesting, but even as a five-year-old Return of the Jedi never left the same impression on me. In fact, I taped over the first 25-minutes of my Return of the Jedi recording with an episode of Super Dave Osbourne around 1990 — nothing of note happened until Han comes out of the carbonite around the 25-minute mark anyway, right?

The main thing I watched it for as a kid were the scenes between Luke, Vader and the Emperor, and the space battle, and those continue to be the highlights for me as an adult. Over time, I have found the behind-the-scenes history and context that the film was made in to be as interesting as the film itself, which is the sort of stuff you tend to be oblivious to as a kid. I think I also became aware of the unevenness of the film, having both the best and worst scenes in the trilogy — something I couldn’t articulate as a child, I just knew it didn’t quite grab me like the other two except for certain parts. Still, there wasn’t a Star Wars trilogy without Return of the Jedi, so every film in the trilogy was essential and considered a classic, you couldn’t just omit one from your personal pantheon, you took the whole trilogy or you took nothing. I do recall a few of my friends telling me around the age of 8 or 9 that Jedi was their favorite.

O’Connell: I was seven years old when I saw Return of the Jedi at the Regal Cinema in Cranleigh, Surrey. It was a glorious 1936 monoplex with one screen, one confectionary kiosk and one film playing at any time. Seeing the illuminated yellow marquee with those big black letters spelling out the name of a film that was finally on my doorstep was nothing short of wondrous. One of my vivid memories involves speeding to the restroom for a pee break (I waited until Yoda had passed to show some respect — but the Dr. Pepper intake was killing me). Whilst I stood in the freezing cold and vintage tiled urinal I could hear Alec Guinness booming around me with his Jedi master advice. I can still see the beams of Obi-Wan’s close-ups emanating from the projection room as I raced back to my seat and the film cut through the smoke-filled theater like a massive R2 unit hologram.

Both then and now, I greatly cherish this film, its rich production, its heroic swagger, its sense of optimistic finality, the kinetic and physical set-pieces and the amount of artillery and vessels that Marquand, Lucas and their teams blessed the film with. That is all heady stuff to a seven-year-old with his own artillery of plastic toys from the film waiting at home to be even more relevant after seeing Return of the Jedi.

Stevens: I saw Return of the Jedi at the Romford Odeon a week after it opened. Before the Internet there was less of a culture of counting down the days to the release of a film. I emerged from the cinema believing the film to be the best of the trilogy. I had actually been disappointed as a ten-year old with The Empire Strikes Back and my thirteen-year-old self thought that Return of the Jedi had undone the damage. It had been so action packed, funny and incredibly dramatic. It answered all of my questions in a satisfying way and left me on a total high. I watched the film on DVD shortly before answering these questions and quite honestly I can’t really see what some people have against it. The Ewoks are cited by many but they should perhaps accept the furry creatures for what they are and concentrate on the film’s other themes. I am courting controversy but for me The Empire Strikes Back is slower and more somber than Return of the Jedi but it is not a great deal deeper. The vision in the cave is carried to its conclusion with Luke staring at his own mechanical hand when he is tempted to kill his father. The deepest concept in Return of the Jedi is that Luke finds that Princess Leia, a woman that he loved romantically is actually his sister. There are ramifications for Leia too considering her treatment at the hands of her own father. Few cinematic moments can compare to Luke burning Darth Vader’s armor.

![A frame from Return of the Jedi]()

Coate: In what way is Jedi significant?

Kaminski: Again, it did things that no movie had done before, such as an ambitious and expensive three-film arc that had a beginning, middle and end. After Empire Strikes Back came out, the storyline could have been stretched out over an infinite number of sequels that kept introducing new plots and characters like an ongoing soap opera, and that was the plan at the time of writing Empire, but from a narrative point of view it is Return of the Jedi that solidified the Star Wars series as a deliberate and finite storyline with a defined and logical arc. As much as the writing of the film gets criticism, it is also remarkable for its larger narrative achievement, which also built roots for sequels, prequels and spinoffs with such a good balance between subtlety and obviousness that modern studio executives should still be studying it.

I think, also, from a narrative point of view, it doesn’t get enough credit for the maturity and emotional depth it brought to the final confrontation between Luke and Vader. Their scenes are the best scenes in the entire franchise, and bring a realistic nuance and poignancy to the relationship between a comic-book villain in a cape and mechanical mask and his space-wizard son. Rather than having a more simplistic and action-packed revenge-style final battle, it is hard to think of another series where the hero and villain finally face each other and just talk. The drama going on beneath the surface there is more interesting than the swordfights. I don’t remember anyone making as big a deal out of this fact at the time as it deserves, but perhaps that is why this trilogy was upheld so highly, and why the flaws in this film become underlined, as the film has such high highs.

O’Connell: It re-ignited the box office might of the trilogy. If The Empire Strikes Back confirmed the commerce of the sequel, then Jedi ’83 proved the dollars and interest a good trilogy could generate. Like a great many 1980s sci-fi blockbusters — and even those that got less noticed — they are instrumental stepping stones in the evolution of visual FX and franchise productions. A lot of films pushed the envelope for those key effects houses throughout California and San Francisco. Return of the Jedi saw a scaling up of those tricks and inventions. One massive Imperial ship slicing across the screen six years before was no longer enough. Now audiences were witnessing multiple ships cascading in all directions, varying scales of battle, even newer camera motion controls and a wholly balletic battle. That beat when the Millennium Falcon soars inside the new Death Star would not have been possible in 1977. Return of the Jedi led to the CGI nursery slopes of Young Sherlock Holmes (1985), which in turn led to Willow (1988), Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) and then Jurassic Park (1993) — the latter of which then gave George Lucas the technical confidence he needed to fully realize the Star Wars prequels. ILM were of course responsible for it all and pushing the FX envelope on Return of the Jedi — that took its key turn in that Darwinian progression of 21st Century visual effects.

Jedi ’83 also has great significance in the history of franchise cinema. What the film represented for the history of pop cultural merchandise alone is highly significant — with an all-out plastic attack on kids toyboxes and home-video rental markets. It was also the last era of keeping a rumor lid on a big movie’s production. Blue Harvest was the film’s location alias (a tic that continues on Star Wars movies to this day) and it now symbolizes a pre-Internet time when spoilers on a franchise movie could be kept quiet. Add to that a cracking, pounding and fiercely paced score by John Williams who was Oscar nominated again for his composing — and you have a grand summer blockbuster whose popularity continues thirty-five years later.

More crucially, Return of the Jedi is also a masterpiece of franchise editing. Its pace and sense of story purpose comes into its own throughout that last, frenetic epic act. The final, split-action battles in space, the Falcon and on Endor are there in many a franchise sequel since (The Return of the King, Avengers: Infinity War). But the difference is that Episode VI didn’t drop the story ball. Every beat, incident and look matters and propels the narrative on. In trying to better Jedi ’83, many a film since has fallen victim to its own digital devastation and carnage.

Stevens: It was difficult for Return of the Jedi to secure a legacy as a “significant” motion picture and that was not the intention of George Lucas and company when they embarked on its making. The film could not have had the freshness of A New Hope or the maturity of The Empire Strikes Back. It did however set a high bar in the realm of action, excitement and comedy; all of the elements that it was intended to deliver. The film was also instrumental in its advancement in special effects. It is challenging even today to spot the joins between the live-action Endor sequences and the animated walkers. The space battle scenes are still a wonder.

![A scene from Return of the Jedi]()

[On to Page 4]

[Back to Page 3]

![A scene from Return of the Jedi]()

Coate: Was Richard Marquand a good choice to direct?

Kaminski: I think he was an appropriate choice given what George Lucas wanted, and that is an important distinction to remember. I don’t feel that he directed the film with the style and visual flair that Kershner brought, but I think Marquand did the best job anyone could. Lucas wanted the film done quickly and without great on-set cost, so the mandate was to film in quick set-ups, which is why the film has a rather flat and dull look to it, without much camera movement and intermixing between scene blocking and camera position, instead using simple, locked off angles without elaborate lighting so the film could be shot fast and then driven by editing. To be fair to Lucas, this is the exact same manner Star Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark were made in, so there was fantastic precedent; Empire Strikes Back looks great because the film went so far over budget and schedule, and Jedi had a budget of about $30 million as it was, making it one of the most expensive films of its time even if everything went according to plan.

You also have to consider the script Marquand was working with, and if Jedi invites some criticism in story, character or dialogue, these are outside of his influence. His main area of influence — the performances — are as good as they can be with the script he had, and when the script is really good Marquand really delivers, as in the case of the scenes with Luke and Vader. The live-action scenes are directed competently, and if the cinematography looks like a made-for-television movie the visuals are made up for by ILM’s magic.

I think Marquand gets a bit short-changed because his life was tragically cut short and so his presence in the history of the series is often overlooked.

O’Connell: George Lucas hankered after Steven Spielberg to direct Return of the Jedi. Could you imagine a Spielberg Star Wars movie?! Sadly, Directors Guild stipulations and politics stopped that from ever happening and the Welsh Richard Marquand ended up taking on the baton from Irvin Kershner. Marquand was a British TV director whose 1981 thriller Eye of the Needle got the attentions of Lucasfilm and its producers.

Sadly, his canon of movie work was short-lived as Marquand prematurely passed away in 1987. It is safe to say what he gave the film was a sense of control. It was probably no easy task to take on the mantle after A New Hope and The Empire Strikes Back. Alongside the challenges of fan expectation, Marquand not only came into a unit made up of a cast and crew who were suddenly getting a new teacher in year three, he had to no doubt contend with the demands of a sci-fi opera of this nature. Yet — even with those conditions and the understandable twitching of franchise flame holder George Lucas — Marquand created a movie that holds together admirably. After the wilfully enclosed and sparse environs and emotions of Empire, Marquand opens out Return of the Jedi with a big scale intent. As soon as we start we are on an expansive and renovated Death Star, the droids are lone figures again in a sea of sand and the full might of the Empire and Rebellion are finally laid bare. Yes, Han Solo’s role could be more influential, and Leia loses that sense of fight from before. Yet, Marquand successfully spins all the requisite plates — and ends up with a fully-fledged intergalactic war movie those yellow crawls had been promising since May 1977. It keeps its soul, humor, and warmth in its sights at all times — despite multiple narratives all vying for attention and their big conclusions. Marquand is responsible for that. The fact that Lucas never allowed another director to take on an episode on his watch may speak certain volumes, but that may not be solely down to Richard Marquand himself.

Stevens: A lot has been written about George Lucas steering clear of using directors from the Directors Guild of America, so he had to choose from a fairly short list of capable candidates. In any case a Star Wars movie is so tightly scripted and storyboarded that it hardly requires any direction, unless in the mode of Irvin Kershner, the person at the helm decides to improve the material they’ve been provided with. Richard Marquand stuck to the script (which was perhaps unavoidable with Lucas over his shoulder) but he put his stamp on the film nonetheless. In the pre-production planning Marquand fine-tuned the script with George Lucas and Lawrence Kasdan. Marquand was also attentive to the acting. There was an incident where Carrie Fisher was standing in her Boushh costume like a soldier on parade but Marquand told her to be stealthier. It could be argued that Marquand could have drawn out better performances, especially from Harrison Ford but if an actor is uncommitted there must be only so much a director can do. Lucas himself was present at much of the filming and is not known for his communication with the cast. Overall I think that Richard Marquand did an excellent job and perhaps elevated the film by some degree from the pulp that was in the script.

Coate: Where do you think Jedi ranks among the original trilogy of films? Among the entire saga?

Kaminski: On a personal level, I consider it easily the most flawed of the original three, but it continues the story of Empire Strikes Back and has characters I already love — because of this, it rides on the coattails of Empire and overcomes flaws that would otherwise seriously harm the film. I always have a hard time placing those good-but-not-quite-great Star Wars films like Revenge of the Sith, Return of the Jedi, Force Awakens or Rogue One and Last Jedi. To me, there are only two great Star Wars films — the original and Empire Strikes Back — and then everything sort of falls in the middle, with Phantom Menace and Attack of the Clones way down at the bottom. I think Return of the Jedi is armed with a secret weapon that none of the other films have though, in that despite having flaws like most of the other films, it gets lumped into the pantheon of Star Wars and Empire by virtue of being the conclusion to the characters and narrative of those films, whereas something like Revenge of the Sith has the opposite problem and has to fight against its ties to two films that failed to develop compelling plot and characters. If J.J. Abrams doesn’t drop the ball with Episode IX I think the new trilogy could stand up fairly well, but nothing will ever come close to that first trilogy, because, well, it’s the first. It did everything for the first time. And as I mentioned — for all its flaws, there is no Star Wars trilogy without Return of the Jedi.

O’Connell: It is a hard trilogy to emerge as victor when you have A New Hope and The Empire Strikes Back in your group too. The original trilogy especially are all very different movies with unique parameters and story needs. Return of the Jedi is a masterclass in movie production, effects, modeling, editing and design. Revenge of the Sith, Rogue One and no doubt Episode IX all echo the adventure and genre achievements of Star Wars ’83. And in a movie era of comic book franchises that don’t know how to conclude as separate, standalone movies or even sagas, Return of the Jedi is an ever valuable blueprint in how to conclude with a swagger, confidence and narrative urgency. One observation about the film is how confident it is with its scope, story requirements and audience expectations. One could observe that no Star Wars film since has been so successful with its three act intent and ability to juggle its disparate story elements.

Stevens: To my mind Return of the Jedi is on balance, on a par with its forbears in the trilogy. Each film delivers its own unique package. It’s a common view that the third chapter of the original trilogy is the weakest but now that everyone knows the outcome of the film, only the first time viewer of Return of the Jedi can be kept in suspense. Even then, it is unlikely for people not to know that Darth Vader is Luke’s father, that the Death Star was destroyed and the rebels won (sorry if that’s a plot spoiler for anyone).

![A scene from Return of the Jedi]()

Coate: Do you have a preference for the Original or Special Edition? In what way was the Special Edition special?

Kaminski: The Special Edition of the film as it currently stands (2011 Blu-ray) is unwatchable to me because of the ending of the film, more so than Han shooting second which I have an easier time overlooking. I don’t complain much about my favorite franchise being “ruined” like you see so many fans these days, who either are new to their fandoms themselves or have very short memories, but the ending of the film — the ending of the trilogy, when the full meaning of the saga comes to crystallization — has been muddled with changes that completely take one out of the experience, as Darth Vader shouting “Noooo” in a reprisal of a dramatic deflation from Episode III notorious for being unintentionally comedic, and the appearance of Hayden Christensen in place of the redeemed Sebastian Shaw that we saw unmasked a few minutes prior, which makes no sense at all and undermines the arc of Anakin’s character. But I could take the 1997 version, which has some okay additions, especially in the expanded ending which makes better sense in the context of the larger series of today (the 1997 version also lacks the Jar Jar inclusion of 2004’s revision). The new Jedi Rocks dance musical is distractingly bad, but I always thought Lapti Nek was pretty embarrassing too. I honestly do believe Lucas was intentionally trolling the fans with his late addition of Darth Vader shouting “Noooo” in 2011, knowing that it had already become a meme making fun of his writing and directing in Revenge of the Sith. Lucas sometimes holds grudges with a mischievous sense of humor, as when he was photographed on the set of Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull a couple years earlier wearing a “Han Shot First” t-shirt.

O’Connell: I am not someone who automatically neck-chokes the Special Editions to the floor. It is sometimes overlooked how George Lucas’s insistence on updating and improving the original trilogy is why we have Star Wars movies today. Some fans may not have liked the new additions and quirks, but they spurred on new audiences to engage with the movies at home and at the movies. The 1997 Special Editions particularly proved the box office love for these films. Imagine if Lucas and Lucasfilm hadn’t renovated the original trilogy at all (which was something he was doing from the first week of release of A New Hope — for reasons of getting it right, not tampering). I am not so sure younger audiences today would fall in love with the original trilogy in its original form had Lucas not upgraded the visuals, sounds and effects to progress and evolve with the times and to feel and operate like non-Eighties movies.

But yes — the originals are the best! The new flourishes of Return of the Jedi — the Palace aliens breaking the fourth wall, the new Max Rebo Band number, the tulip-tentacled Sarlaac Pit, the new Ewok celebration tune and even the non-Star Wars-y explosive ripples of the Death Star’s destruction — do not add anything that was not there to begin with. But they justified new cinema releases which in turn led to new cinema audiences, new fans, new product, and new trilogies.

Stevens: Personally speaking I don’t consider the Special Edition to be all that special. There wasn’t anything in the film that needed fixing. Two of the changes are simply abysmal; the song and dance routine in Jabba’s Palace and the addition of Hayden Christensen’s ghost at the finale (not to mention changing the closing theme and scenes of celebration around the galaxy). I never watch the Special Edition at home.

![A 70 mm film frame for Return of the Jedi]()

Coate: What is the legacy of Return of the Jedi?

Kaminski: I think you have to put Return of the Jedi in the context of when it was made and what it was intended to do. It wasn’t the crowing epic of the six-chapter saga of Anakin Skywalker, it was meant to be the closing sequel to Star Wars that wrapped up the story and character arcs begun in that film in a story that was befitting the spirit of Star Wars. The first act at Jabba’s Palace and the corny original closing of “Yub Nub” strike younger viewers as out of place, but I think those two elements are the best examples that illustrate the original context of Return of the Jedi. The Jabba’s Palace sequence lets us see all our heroes together again making wisecracks with each other in a fun and exciting sequence after they were split up for most of Empire Strikes Back, while also celebrating the return of fan-favorite Han Solo, and Yub Nub is a fun and funny send off to our friends as the series ends with a chorus literally singing “celebrate the love” as our heroes clap around a camp fire. As the conclusion to the lighthearted and funny original Star Wars, it balanced the serious melodrama of Empire against that helluvvatime-at-the-movies sense of glee the original film had. George Lucas has said that he wanted audiences leaving the theater in 1983 to feel totally uplifted and in high spirits and in the mood to celebrate, just as the state we leave the characters, and I think that aspect has been lost now that the scale and scope of the Star Wars saga has outgrown that trio of films. You have Chewie and Han dancing with Ewoks and playing the drums on the helmets of stormtroopers, and then the film takes a quiet moment as the spirit of Anakin, Yoda and Obi-Wan appear to give Luke a thumbs up before he rejoins his friends and the music crescendos with “celebrate the love.” I think the original theatrical ending perfectly encapsulates how to appreciate the purpose and expectation in which the film was made, because it doesn’t exist in that context any more. It also has to be seen as a reaction against the departure of style and content that Empire brought, which is partly why it recycles so much.

O’Connell: The last act of Rogue One, the underworld gangsters of Solo, the production golds and reds of The Last Jedi, that the prequels were as much a Palpatine backstory as an Anakin Skywalker one, and that franchise mainstay of good people improvising as best they can with what they can to defeat evil. Add to that — the warm memories of Star Wars younglings who endlessly recreated those Jabba’s Palace scenes, the Speeder Bike chases around the school yard and the Sarlaac Pit which saw many a bedsheet rolled into a deadly tentacle and thrown down the stairs. It was a glorious entry point for those sky kids who missed the theatrical runs of A New Hope and The Empire Strikes Back. In a year of threes — Jaws 3-D, Amityville 3-D, Superman III, Smokey and the Bandit 3 — for one generation Return of the Jedi represents their beginning of Star Wars fandom, not the end of it.

Stevens: With its dramatic and satisfying conclusion of the overall plot and its upbeat finale, Return of the Jedi set the future of the Star Wars brand on an extremely sure footing and ensured that the trilogy would be regarded as one of the greatest of all time. That would not have transpired if the third chapter had been lackluster and had left audiences unmoved. The law of diminishing returns usually applies to film series but this is not the case with Return of the Jedi, judging by the audience reaction and box office takings in comparison to Empire. In the formative years of “blockbuster” films Return of the Jedi proved the viability of film series and the success of the Star Wars trilogy is something that film makers have strived to emulate ever since.

Coate: Thank you — Michael, Mark, and Craig — for sharing your thoughts about Return of the Jedi on the occasion of its 35th anniversary.

--END--

IMAGES

Selected images copyright/courtesy Lucasfilm Ltd., 20th Century Fox Film Corporation, 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment, The Walt Disney Company.

![A scene from Return of the Jedi]()

SOURCES/REFERENCES

The primary references for this project were regional newspaper coverage and trade reports published in Billboard, Boxoffice, The Hollywood Reporter and Variety. All figures and data included in this article pertain to the United States and Canada except where stated otherwise. This work is based upon articles by same author previously published at TheDigitalBits.com, FromScriptToDVD.com, In70mm.com and CinemaTreasures.org.

![More original screenings of Return of the Jedi in 1983]()

SPECIAL THANKS

Don Beelik, Raymond Caple, Andrew Crews, Sheldon Hall, John Hazelton, Bobby Henderson, Michael Kaminski, Bill Kretzel, Mark Lensenmayer, Monty Marin, W.R. Miller, Mark O’Connell, Jim Perry, Cliff Stephenson, Craig Stevens, and an extra special thank-you to all of the librarians who helped with this project.

IN MEMORIAM

- Graham Freeborn (Chief Make-up Artist), 1943-1986

- Richard Marquand (Director), 1937-1987

- Douglas Twiddy (Production Supervisor), 1919-1990

- Sebastian Shaw (Anakin Skywalker), 1905-1994

- Jack Purvis (“Teebo”), 1937-1997

- Alec Guinness (“Ben ‘Obi-Wan’ Kenobi”), 1914-2000

- Claire Davenport (“Fat Dancer”), 1933-2002

- Peter Diamond (Stunt Arranger), 1929-2004

- Mary Selway (Casting), 1936-2004

- David Tomblin (First Assistant Director/2nd Unit Director), 1930-2005

- James Glennon (Location Director of Photography), 1942-2006

- Alan Hume (Director of Photography), 1924-2010

- Fred Hole (Art Director), 1935-2011

- Ralph McQuarrie (Production Illustrator), 1929-2012

- Kay Freeborn (Make-up Artist), 19??-2012

- Stuart Freeborn (Make-up Designer), 1914-2013

- Kenny Baker (“R2-D2” and “Paploo”), 1934-2016

- Kit West (Mechanical Effects Supervisor), 1936-2016

- Carrie Fisher (“Princess Leia”), 1956-2016

-Michael Coate

Michael Coate can be reached via e-mail through this link. (You can also follow Michael on social media at these links: Twitter and Facebook)

![Return of the Jedi one sheet]()

“The fine Dutch director Paul Verhoeven presents what could have been another high-tech assault picture with fresh visuals and a refreshing sense of humor, especially about big business.” — Gene Siskel, Chicago Tribune

“The fine Dutch director Paul Verhoeven presents what could have been another high-tech assault picture with fresh visuals and a refreshing sense of humor, especially about big business.” — Gene Siskel, Chicago Tribune

![RoboCop newspaper ad]() DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

Coate: Where do you think RoboCop ranks among Paul Verhoeven’s body of work?

Coate: Where do you think RoboCop ranks among Paul Verhoeven’s body of work?

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

Christie: Dalton was famously an admirer of Ian Fleming’s fiction, and he is known to have studied the original Bond novels and short fiction closely when preparing to take on the part. Thus Dalton’s Bond was much more of a reluctant hero in comparison to Roger Moore’s incarnation, and there was an undeniable influence of the Fleming Bond in the way that the veteran agent was not always comfortable with carrying out his orders. Though he hits the ground running, thanks in no small part to a pre-credits sequence that hurls him straight into the thick of the action, it is interesting to see how Dalton’s take on the character quickly establishes itself as no-nonsense, slightly jaded, and considerably more contemplative than many of his predecessors. Whereas Sean Connery’s Bond appeared as more or less a fully-formed character from the earliest scenes of Dr. No, and George Lazenby faced the challenge of establishing himself as a successor while putting his own stamp on 007 in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, Moore had a much more stately introduction to the Bond role in Live and Let Die, easing himself into the character rather more gradually. But Dalton appeared determined to waste no time in establishing his troubled, world-weary take on Bond and — though he often seemed less than comfortable with the film’s sparing moments of light-heartedness and occasional punning witticisms — he performs with great confidence and lends this brooding, discontented figure a laudable depth of character throughout.

Christie: Dalton was famously an admirer of Ian Fleming’s fiction, and he is known to have studied the original Bond novels and short fiction closely when preparing to take on the part. Thus Dalton’s Bond was much more of a reluctant hero in comparison to Roger Moore’s incarnation, and there was an undeniable influence of the Fleming Bond in the way that the veteran agent was not always comfortable with carrying out his orders. Though he hits the ground running, thanks in no small part to a pre-credits sequence that hurls him straight into the thick of the action, it is interesting to see how Dalton’s take on the character quickly establishes itself as no-nonsense, slightly jaded, and considerably more contemplative than many of his predecessors. Whereas Sean Connery’s Bond appeared as more or less a fully-formed character from the earliest scenes of Dr. No, and George Lazenby faced the challenge of establishing himself as a successor while putting his own stamp on 007 in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, Moore had a much more stately introduction to the Bond role in Live and Let Die, easing himself into the character rather more gradually. But Dalton appeared determined to waste no time in establishing his troubled, world-weary take on Bond and — though he often seemed less than comfortable with the film’s sparing moments of light-heartedness and occasional punning witticisms — he performs with great confidence and lends this brooding, discontented figure a laudable depth of character throughout.

Coate: Is it beneficial to watch the episodes in their original production/broadcast order?

Coate: Is it beneficial to watch the episodes in their original production/broadcast order?

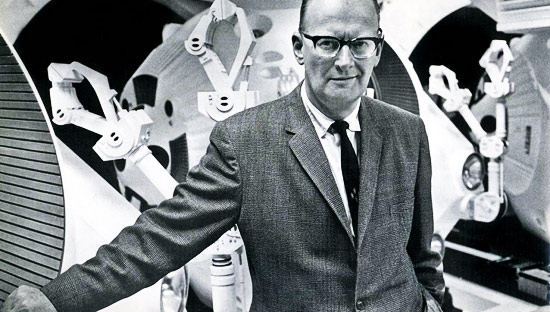

Chris Barsanti is the author of The Sci-Fi Movie Guide: The Universe of Film from Alien to Zardoz (Visible Ink; 2014).

Chris Barsanti is the author of The Sci-Fi Movie Guide: The Universe of Film from Alien to Zardoz (Visible Ink; 2014). Raymond Benson is a college-level film history instructor (who includes a screening of 2001: A Space Odyssey in his curriculum) and author of three-dozen books.

Raymond Benson is a college-level film history instructor (who includes a screening of 2001: A Space Odyssey in his curriculum) and author of three-dozen books. Peter Krämer is the author and editor of eight academic books, including the BFI Film Classics volume on 2001: A Space Odyssey (published in 2010).

Peter Krämer is the author and editor of eight academic books, including the BFI Film Classics volume on 2001: A Space Odyssey (published in 2010).

Peter Krämer: As one of the greatest movies of all time. As a key source for much of the science fiction cinema of recent decades, from Star Wars to Avatar and beyond. As a film that has dazzled and inspired people for many years.

Peter Krämer: As one of the greatest movies of all time. As a key source for much of the science fiction cinema of recent decades, from Star Wars to Avatar and beyond. As a film that has dazzled and inspired people for many years.

Benson: I saw it on first release in Odessa, Texas, with my father, in 70mm. I was 13 years old. I already loved movies and was just beginning to have an appreciation for the many aspects that went into the making of a film — not just whether or not it entertained me. I believe that 2001 gave me a better understanding of what “Directed By” means. From that point on, I became interested in who Stanley Kubrick was. As I grew older, I sought out his earlier films and kept up with his career until the end. Curiously, when I first saw 2001, I had no problem “getting” it. As we were leaving the theater, my father asked me if I understood the movie — he hadn’t, although he found it amazing and was entranced by the picture all the way through. I explained my interpretation to him, and he was impressed. During that first release, all my friends my age “didn’t understand it,” but they all liked it. It was too much of a never-before-seen cinematic experience not to like.

Benson: I saw it on first release in Odessa, Texas, with my father, in 70mm. I was 13 years old. I already loved movies and was just beginning to have an appreciation for the many aspects that went into the making of a film — not just whether or not it entertained me. I believe that 2001 gave me a better understanding of what “Directed By” means. From that point on, I became interested in who Stanley Kubrick was. As I grew older, I sought out his earlier films and kept up with his career until the end. Curiously, when I first saw 2001, I had no problem “getting” it. As we were leaving the theater, my father asked me if I understood the movie — he hadn’t, although he found it amazing and was entranced by the picture all the way through. I explained my interpretation to him, and he was impressed. During that first release, all my friends my age “didn’t understand it,” but they all liked it. It was too much of a never-before-seen cinematic experience not to like.

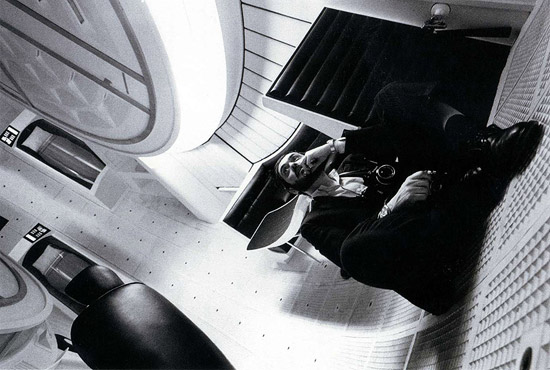

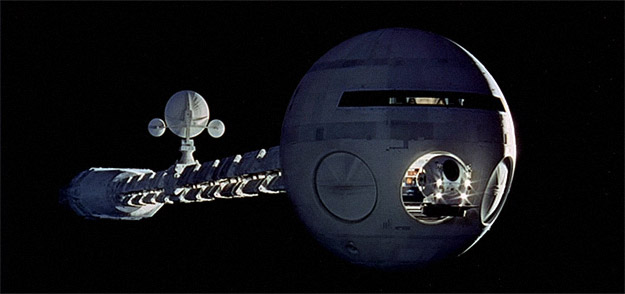

Krämer: I don’t think one can say that Kubrick was “chosen” to direct 2001. He developed the whole project from scratch. Soon after the release of Dr. Strangelove, he contacted Arthur C. Clarke, one of the world’s leading science fiction writers and also the author of many popular science books, and asked him whether he wanted to collaborate on developing a story for a science fiction film which would center on humanity’s encounter with an extraterrestrial civilization.

Krämer: I don’t think one can say that Kubrick was “chosen” to direct 2001. He developed the whole project from scratch. Soon after the release of Dr. Strangelove, he contacted Arthur C. Clarke, one of the world’s leading science fiction writers and also the author of many popular science books, and asked him whether he wanted to collaborate on developing a story for a science fiction film which would center on humanity’s encounter with an extraterrestrial civilization.

Coate: Can you describe what it was like seeing Live and Let Die for the first time?

Coate: Can you describe what it was like seeing Live and Let Die for the first time?

Coate:

Coate:

Coate: Where do you think Dazed and Confused ranks among Richard Linklater’s body of work?

Coate: Where do you think Dazed and Confused ranks among Richard Linklater’s body of work?

John Scoleri: I think the ideal way to remember the film on its 50th anniversary was to see the Museum of Modern Art’s 4K restoration on the big screen. I was honored to attend the 50th anniversary screening of the film a few weeks ago at the Byham Theater (formerly the Fulton) in downtown Pittsburgh, in the same theater where the film premiered in 1968. The majority of the surviving cast and crew were in attendance, and it was a wonderful way to celebrate the film.

John Scoleri: I think the ideal way to remember the film on its 50th anniversary was to see the Museum of Modern Art’s 4K restoration on the big screen. I was honored to attend the 50th anniversary screening of the film a few weeks ago at the Byham Theater (formerly the Fulton) in downtown Pittsburgh, in the same theater where the film premiered in 1968. The majority of the surviving cast and crew were in attendance, and it was a wonderful way to celebrate the film.

Coate: Can you describe what it was like seeing A Christmas Story for the first time?

Coate: Can you describe what it was like seeing A Christmas Story for the first time?

Coate: Where do you think A Christmas Story ranks among Christmas-themed movies?

Coate: Where do you think A Christmas Story ranks among Christmas-themed movies?

tt’s Northpoint (23) [70mm from Week 2]

tt’s Northpoint (23) [70mm from Week 2]

Coate: Can you recall the first time you saw The Hidden Fortress?

Coate: Can you recall the first time you saw The Hidden Fortress?

Coate: Is The Odd Couple a significant motion picture in any way(s)?

Coate: Is The Odd Couple a significant motion picture in any way(s)?

Coate: What is the legacy of From Russia with Love?

Coate: What is the legacy of From Russia with Love?

Coate: In what way was Olga Kurylenko’s Camille Montes (or Gemma Arterton’s Strawberry Fields) a memorable Bond Girl?

Coate: In what way was Olga Kurylenko’s Camille Montes (or Gemma Arterton’s Strawberry Fields) a memorable Bond Girl?